Trade Secret or Patenting

Two types of intellectual property for protecting your food product are: patents and trade secrets. If patent protection is not available, then the best approach is to contact the attorneys of Garcia-Zamor to set up a trade secret strategy for protecting your food product.

Patent Protection for Your Food Product

To be patentable, a food product —like all other inventions—must be “novel” and “nonobvious.” There are different strategies for patenting food products, which involve focusing your patent application on:

- the processing steps that are necessary to prepare your food product;

- the processing steps that are used to increase shelf life of your food product;

- the shape of your food product as presented to the consumer;

- the process of replicating a known food item while achieving a new goal (methods of processing to make your food product, healthier, fat-free, meatless, etc.); and

- the chemical composition of your food when an artificial process is used to manufacture food products, such as Bang Energy drinks, Quest protein bars, and the like.

When your new food product does not provide a basis for filing a patent application in line with one of the above strategies, it may be more difficult to obtain patent protection. Not properly focusing a patent application for a food product increases the risk of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) rejecting your application as a mere recipe. Once the USPTO has taken the position that your new food product is a mere recipe (with nothing special), it can be difficult to impossible to prove that your food product is not just an obvious adjustment of a previously known recipe.

Processing Steps to Prepare Your Food Product

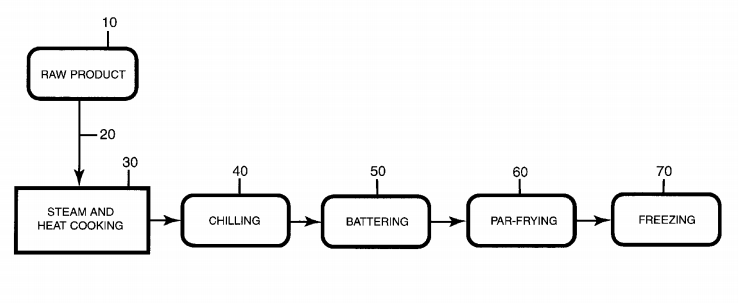

When recipes qualify for patent protection, their patentability is often because of their processing. For example, US Patent 6,117,463 protects a commercial process for preparing battered food. The schematic shown below is a figure from the patent that outlines the process.

US6117463

Processing Steps to Increase Shelf Life

A process or combination of ingredients that increases the shelf life of food could also be patentable. US Patent 4,937,092 protects a way of increasing the shelf life for refrigerated fish. The most broad claim is set forth below and lists the chemicals that are used to increase shelf life:

Claim 1: A composition for improving the shelf life of fish fillet comprising:

(a) from about 40% to about 55% of an alkali metal tripolyphosphate hydrated with lemon juice solids;

(b) alkali metal acid pyrophosphate in an amount ranging from about 55% to about 40%, said amount being sufficient to provide a treatment solution having a pH within the range of from about 5.5 to about 6.5; and

(c) a sorbate antimicrobial agent in an amount ranging from about 4% to about 8.5%, said amount being sufficient with the alkali metal tripolyphosphate hydrated with lemon juice solids and the alkali metal acid pyrophosphate to extend the shelf life of the fillet over the life of untreated fish fillet; said percentages being based on the total dry weight of said composition.

The Shape of Your Food Product

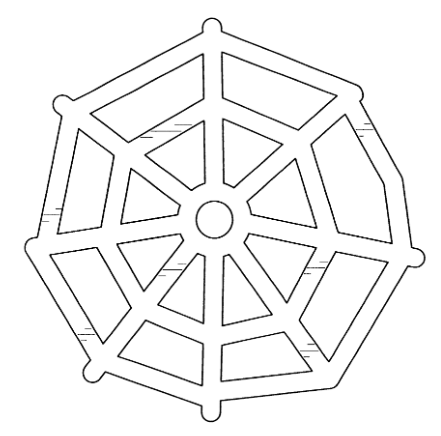

Altering the shape of a food may also earn a patent in some cases. Design patents are used for protecting the way an invention looks. Kraft Foods, for example, has dozens of design patents for shaped pasta. US Design Patent 526461S1 protects Kraft’s spider web shaped pasta. The pictures shown below are figures from the patent demonstrating the claimed design.

USD526461S1

Processing of Replicating a Food Item / Chemical Composition of Your Food Product

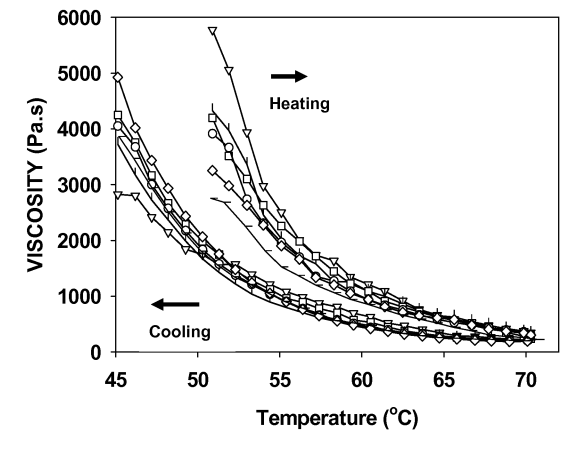

Making foods healthier, meatless, dairy-free, or gluten-free may also qualify for patent protection. Take, for example, a patent for improving low-fat and non-fat cheese. US Patent 8,623,435 protects a method for making low-fat and fat-free cheese. The most broad claim is set forth below and sets forth the chemical composition of the protected food product:

Claim 1: A method for making processed cheese, comprising: a) acidifying a reduced-fat milk source to obtain a cheese base comprising particles; and b) adding between about 0.4 wt.% to about 8 wt.% glycerides to the cheese base to obtain processed cheese, wherein the glycerides comprise between about 40% to about 80% of monoglycerides relative to the amount of glycerides and between about 20% to about 60% of diglycerides relative to the amount of glycerides.

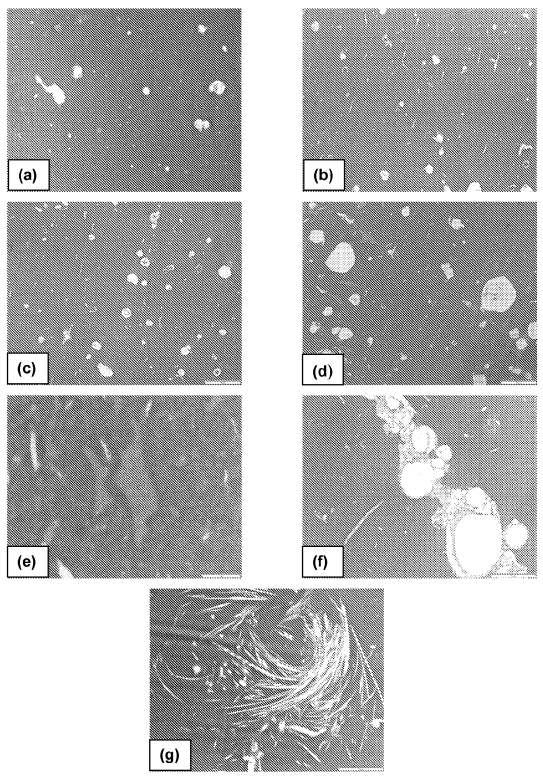

The following figures demonstrate qualities and processing parameters for the above claimed food product.

“Three may keep a secret, if two of them are dead.”

– Benjamin Franklin

Trade secrets can be valuable for preventing others from learning how your food product is made by wrongfully obtaining the information. You could also use your trade secret as part of your advertising campaign. For instance, KFC, Coca-Cola, and Dr. Pepper have used their trade secrets as a marketing tool. For example, the ingredients list for McDonald’s Big Mac “special sauce” is protected as a trade secret, as well.

Informally speaking, for your food product to qualify for trade secret protection, its composition and/or how it is processed must meet the following three elements:

- The composition and/or how it is processed must actually be a secret.

- The composition and/or how it is processed must be of commercial value to your competition.

- You must take reasonable steps to protect information regarding the composition and/or how your food product is processed. **

To establish a trade secret protection strategy, it is important to contact the attorneys of Garcia-Zamor to prepare the necessary contracts, procedures, and employee agreements before your information is shared with the competition. It’s important to understand that trade secrets do not prevent others from independently creating or reverse engineering your food product.

Taylor Hallowell is a specialist in intellectual property at Garcia-Zamor Intellectual Property Law, LLC. She is currently pursuing her Juris Doctorate at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law in Baltimore, Maryland. She received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Biology from Amherst College in Massachusetts. Ms. Hallowell primarily focuses on contracts, discovery, and patents, mainly in the fields of mechanical technologies.

** A less informal definition of what qualifies as a trade secret is set forth by the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA). The UTSA defines a “trade secret” as “information, including a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique, or process that derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to, and not being readily ascertainable by proper means by, other persons who can obtain economic value from its disclosure or use; and is the subject of efforts that are reasonable under the circumstances to maintain its secrecy.” Emphasis added.